Migraine headaches

Highlights

Migraine Triggers

Migraines can be triggered by many everyday things. Different people respond to different triggers, so it is important to track your migraine patterns to help you avoid things that set off your migraine attacks. Common migraine triggers include:

- Emotional stress

- Intense physical exertion

- Abrupt weather changes

- Bright or flickering lights

- High altitude

- Travel motion

- Lack of sleep

- Skipping meals

- Odors

- Certain foods and beverages (aged cheese, chocolate, red wine, beer, coffee, and many others)

- Food additives or preservatives (such as nitrates and monosodium glutamate)

Migraine Treatment Approaches

Migraines need a two-pronged approach: Treatment and prevention. Treatment uses medications that provide quick pain relief when attacks occur. These drugs include pain relievers such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic), triptans such as sumatriptan (Imitrex, generic), and ergotamine drugs.

Preventive strategies begin with non-drug approaches, including behavioral therapies and lifestyle changes. If headache attacks continue to occur at least once a week, or if your attacks do not respond well to treatment, your doctor may recommend you try preventive medication.

Migraine Prevention Guidelines

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) updated its guidelines for prevention of migraine in adults. The main treatments recommended by the AAN for migraine prevention are:

- Anti-seizure drugs [usually divalproex (Depakote, generic), valproate (Depacon, generic) or topiramate (Topamax, generic)]

- Beta-blocker drugs [propranolol (Inderal, generic), timolol (Blocadren), or metoprolol (Lopressor, generic)]

- The triptan frovatriptan (Frova) for menstrual migraine

- The herbal remedy butterbur (Petasites hybridus)

Antidepressants [amitriptyline (Elavil, generic) or venlafaxine (Effexor, generic)] are also considered for migraine prevention. OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections are approved for prevention of chronic migraine.

Introduction

Migraine Headaches

Migraine headaches are a type of neurovascular headaches, a category that also includes cluster headaches. Doctors believe that neurovascular headaches are caused by an interaction between blood vessel and nerve abnormalities. Migraine headaches are the second most common type of primary headache after tension headaches. A primary headache is a headache that is not caused by another disease or condition. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #11: Headaches - tension and Report #99: Headaches - cluster.]

Migraine headaches are characterized by throbbing disabling pain on one side of the head, which sometimes spreads to affect the entire head. In fact, migraine comes from the Greek word hemikrania, meaning “half of the head.”

Migraines are classified as occurring either:

- With aura (previously called classic migraine) or

- Without aura (previously called common migraine)

Auras are sensory disturbances that occur before a migraine attack that can cause changes in vision, with or without other neurologic symptoms. [For more information on auras, see Symptoms section of this report.]

Episodic and Chronic Migraine

Migraines typically occur as isolated episodic attacks, which can happen once a year or several times within one week. In some cases, patients eventually experience on-going and chronic migraine (previously called transformed migraine). Chronic migraines typically begin as episodic headaches when patients are in their teens or 20s, and then increase in frequency over time. A headache is considered chronic when it occurs at least half of the days in a month, and often on a daily or near-daily basis.

The majority of chronic migraines are caused by overuse of analgesic migraine medications, both prescription pain reliever drugs and over-the-counter medications. Medication overuse headaches are also called rebound headaches. Obesity and caffeine overuse are other factors that may increase the risk of episodic migraine transforming to chronic migraine.

Chronic migraines can resemble tension-type headaches and it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between them. Both types of headaches can co-exist. In addition to throbbing pain on one side of the head, chronic migraine is marked by gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting. Many patients with chronic migraine also suffer from depression.

Other Types of Migraine

Menstrual Migraines. Migraines are often tied to a woman's menstrual cycle, typically in the first days preceding or beginning menstruation. Estrogen and progesterone fluctuations may play a role. About half of women with migraines report an association with menstruation. Compared to migraines that occur at other times of the month, menstrual migraines tend to be more severe, last longer, and not have auras. Triptan drugs can provide relief and may also help prevent these types of migraines.

Basilar Migraine. Considered a subtype of migraine with aura, this migraine starts in the basilar artery, which forms at the base of the skull. It occurs mainly in young people. Symptoms may include vertigo (a sensation of dizziness), ringing in the ears, slurred speech, unsteadiness, possibly loss of consciousness, and severe headaches.

Abdominal Migraine. This migraine tends to occur in children who have a family history of migraine. Periodic migraine attacks are accompanied by abdominal pain, and often nausea and vomiting.

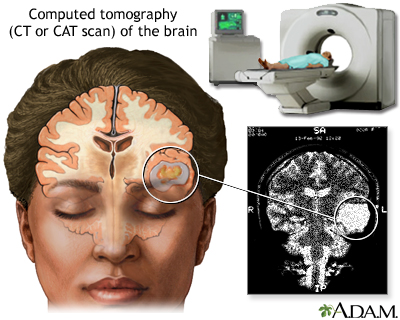

Ophthalmoplegic Migraine. This very rare headache tends to occur in younger adults. The pain centers around one eye and is usually less intense than in a standard migraine. It may be accompanied by vomiting, double vision, a droopy eyelid, and paralysis of eye muscles. Attacks can last from hours to months. A computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be needed to rule out bleeding from an aneurysm (a weakened blood vessel) in the brain.

Retinal Migraine. Symptoms of retinal migraine are short-term blind spots or total blindness in one eye that lasts less than an hour. A headache may precede or occur with the eye symptoms. Sometimes retinal migraines develop without headache. Other eye and neurologic disorders must be ruled out.

Vestibular Migraine. These attacks produce episodic dizziness, which can develop alone or with headache and other typical migraine symptoms. Ringing in the ears (tinnitus) and ear fullness are common.

Familial Hemiplegic Migraine. This is a very rare inherited genetic migraine disease. It can cause temporary paralysis on one side of the body, vision problems, and vertigo. These symptoms occur about 10 - 90 minutes before the headache.

Status Migrainosus. This is a serious and rare migraine. It is so severe and lasts so long that it requires hospitalization.

Causes

The exact causes of migraine headaches are unknown. Doctors think that migraines may start with an underlying central nervous system disorder. When triggered by various stimuli, this disorder may set off a chain of neurologic and biochemical events, some of which subsequently affect the brain's blood vessel (vascular) system.

There is certainly a strong genetic component to migraines. Several different genes are probably involved.

Many brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) and nerve pathway disrupters appear to play a role in causing migraines. They include the neurotransmitter serotonin, magnesium deficiencies, and abnormalities in the channels within cells that transport electrical ions such as calcium.

Migraine Triggers

Many types of events and conditions can alter conditions in the brain and trigger migraines. They include:

- Emotional stress

- Physical exertion (such as intense exercise, lifting, or even bowel movements or sexual activity)

- Abrupt weather changes

- Bright or flickering lights

- Odors

- High altitude

- Travel motion

- Lack of sleep

- Skipping meals

- Certain foods, and chemicals contained in them. More than 100 foods and beverages may potentially trigger migraine headache. Caffeine is one such trigger. Caffeine withdrawal can also trigger migraines in people who are accustomed to caffeine. Red wine and beer are also common triggers. Preservatives and additives (such as nitrates, nitrites, and MSG) can also trigger attacks. Doctors recommend that patients keep a headache diary to track the foods that trigger migraine.

- Fluctuations of female hormones may trigger migraines in women.

Risk Factors

Gender

About 75% of all migraine sufferers are women. During childhood, boys and girls are equally affected. After puberty, migraines are more common in girls. Migraine most commonly affects women between the ages of 20 - 45.

Fluctuations of female hormones, such as estrogen and progesterone, appear to increase the risk for migraines and their severity in some women. About half of women with migraines report headaches associated with their menstrual cycle. For some women, migraines also tend to be worse during the first trimester of pregnancy, but improve during the last trimester.

Age

Migraine headaches typically affect people between the ages of 15 - 55. However, migraine also affects about 5 - 10% of all children. Many children with migraine eventually stop having attacks when they reach adulthood or transition to less severe tension-type headaches. Children with a family history of migraine may be more likely to continue having migraines.

Family History

Migraines tend to run in families. About 70 - 80% of patients with migraine have a family history of the condition.

Medical Conditions Associated with Migraines

People with migraine may have a history of depression, anxiety, stroke, epilepsy, irritable bowel syndrome, or high blood pressure. These conditions do not necessarily increase the risk for migraine, but they are associated with it.

Symptoms

A migraine attack may involve up to four symptom phases: prodrome phase, auras, the attack, and the postdrome phase. These phases may not occur in every patient or every headache.

Prodrome Symptoms

The prodrome phase is a group of vague symptoms that may precede a migraine attack by several hours, or even a day or two. Prodrome symptoms may include:

- Sensitivity to light or sound

- Changes in appetite, including decreased appetite or food cravings

- Thirst

- Fatigue and drowsiness

- Mood changes, including depression, irritability, or restlessness

Aura Symptoms

Auras are sensory disturbances that occur before the migraine attack in 1 in 5 patients. Visually, auras are referred to as being positive or negative:

- Positive auras include bright or shimmering light or shapes at the edge of the field of vision called scintillating scotoma. They can enlarge and fill the line of vision. Other positive aura experiences are zigzag lines or stars.

- Negative auras are dark holes, blind spots, or tunnel vision (inability to see to the side).

- Patients may have mixed positive and negative auras. This is a visual experience that is sometimes described as a fortress with sharp angles around a dark center.

Other neurologic symptoms may occur at the same time as the aura, although they are less common. They may include:

- Speech disturbances

- Tingling, numbness, or weakness in an arm or leg

- Perceptual disturbances such as space or size distortions

- Confusion

Migraine Attack Symptoms

If left untreated, attacks usually last from 4 - 72 hours. A typical migraine attack produces the following symptoms:

- Throbbing pain on one side of the head. Pain also sometimes spreads to affect the entire head.

- Pain worsened by physical activity

- Nausea, sometimes with vomiting

- Visual symptoms

- Facial tingling or numbness

- Extreme sensitivity to light and noise

- Looking pale and feeling cold

Less common symptoms include tearing and redness in one eye, swelling of the eyelid, and nasal congestion, including runny nose. (Such symptoms are more common in certain other headaches, notably cluster headaches.)

Postdrome Symptoms

After a migraine attack, there is usually a postdrome phase, in which patients may feel exhausted and mentally foggy for a while.

Prognosis

For many people, migraines eventually go into remission and sometimes disappear completely, particularly as they age. Estrogen decline after menopause may be responsible for remission in some older women.

Complications

Risk for Stroke and Heart Disease. Migraine or severe headache is a risk factor for stroke in both men and women, especially before age 50. Research indicates that migraine may also increase the risk for other types of heart problems.

Migraine with aura appears to carry a higher risk for stroke than migraine without aura, especially for women. Because of this, it is very important that women with migraine avoid other stroke risks such as smoking and possibly birth control pills. Some studies suggest that people who have migraine with aura are more likely than people without migraine to have cardiovascular risk factors (such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure) that increase the risk for stroke. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #45: Stroke.]

Emotional Disorders and Quality of Life. Migraines have a significant negative impact on quality of life, family relations, and work productivity. Studies indicate that people with migraines have poorer social interactions and emotional health than patients with many chronic medical illnesses, including asthma, diabetes, and arthritis. Anxiety (particularly panic disorders) and major depression are also strongly associated with migraines.

A National Headache Foundation-sponsored survey of migraine sufferers reported that:

- 90% of people with migraines could not function normally on the day of a migraine attack

- 80% experienced abnormal sensitivity to light and noise

- 75% experienced nausea and vomiting

- 30% required bed rest

- 25% missed at least 1 day of work due to migraine in past 3 months

Diagnosis

Anyone, including children, with recurring or persistent headaches should consult a doctor. There are no blood tests or imaging techniques that can be used to diagnose migraine headaches. A diagnosis will be made on the basis of medical history and physical exam, and, if necessary, tests may be necessary to rule out other diseases or conditions that may be causing the headaches. It is important to choose a doctor who is sensitive to the needs of headache sufferers and aware of the latest advances in treatment.

Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine

A diagnosis of migraine is usually made on the basis of repeated attacks (at least 5) that meet the following criteria:

- Headache attacks that last 4 - 72 hours

- Headache has at least two of the following characteristics: Location on one side of the head; throbbing pain; moderate or severe pain intensity; pain worsened by normal physical activity (such as walking or climbing stairs)

- During the headache, the patient has one or both of the following characteristics: Nausea or vomiting; extreme sensitivity to light or sound

- The headache cannot be attributed to another disorder

Headache Diary

The patient should try to recall what seems to bring on the headache and anything that relieves it. Keeping a headache diary is a useful way to identify triggers that bring on headaches, as well as to track the duration and frequency of headache attacks. Some tips include:

- Note all conditions, including any foods eaten, preceding an attack. Often two or more triggers interact to produce a headache. For example, a combination of weather changes and fatigue can make headaches more likely than the presence of just one of these events.

- Keep a migraine record for at least three menstrual cycles. For women, this can help to confirm a diagnosis of menstrual migraine.

- Track medications. This is important for identifying possible medication-overuse (rebound) headache or chronic (transformed) migraine.

- Attempt to define the intensity of the headache using a number system, such as:

1 = Mild, barely noticeable

2 = Noticeable, but does not interfere with work/activities

3 = Distracts from work/activities

4 = Makes work/activities very difficult

5 = Incapacitating

Medical and Personal History

Tell your doctor any other conditions that might be associated with headache, including:

- Any chronic or recent illness and their treatments

- Any injuries, particularly head or back injuries

- Any dietary changes

- Any current medications or recent withdrawals from any drugs, including over-the-counter or natural (herbal or dietary supplement) remedies

- Any history of caffeine, alcohol, or drug abuse

- Any serious stress, depression, or anxiety

The doctor will also need a general medical and family history of headaches or diseases, such as epilepsy, that may increase their risk. Migraine tends to run in families.

Physical Examination

The doctor will examine the head and neck and will usually perform a neurologic examination, which includes a series of simple exercises to test strength, reflexes, coordination, and sensation. The doctor may ask questions to test short-term memory and related aspects of mental function.

Differentiating Between Migraine and Other Types of Headaches

Differentiating Between Migraines and Tension Headaches. Migraine and tension-type headaches have some similar characteristics, but also some important differences:

- Migraine pain is throbbing, while tension-type headache pain is usually a steady ache

- Migraine pain may affect only one side of the head while tension-type headache pain typically affects both sides of the head

- Migraine pain, but not tension-type pain, worsens with head movement

- Migraine headaches, but not tension-type headaches, may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting, sensitivity to light and sound, or aura

[For more information, see In-Depth Report #11: Tension-type headache.]

Differentiating Between Migraines and Sinus Headaches. Many primary headaches, including migraine, are misdiagnosed as sinus headaches, causing patients to be treated inappropriately with antibiotics. Many patients who think they have sinus headaches may actually have had a migraine. It is also possible for patients to have migraines with sinus symptoms such as congestion and facial pressure.

Sinus headaches occur in the front of the face, with pain or pressure around the eyes, across the cheeks, or over the forehead. They are usually accompanied by fever, runny nose or congestion, and fatigue. In sinus headaches, the nasal discharge is thick green or yellow. Nasal discharge in migraines is clear and watery.

A real sinus headache is a sign of an acute sinus infection, which responds to treatment with decongestants and may sometimes require antibiotics. If sinus headaches seem to recur, the patient is likely experiencing migraines.

Imaging Tests

The doctor may order a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test of the head to check for brain abnormalities that may be causing the headaches. Imaging tests of the brain may be recommended if the results of the history and physical examination suggest neurologic problems such as:

- Changes in vision

- Muscle weakness

- Fever

- Stiff neck

- Changes in the way someone walks

- Changes in someone's mental status (disorientation)

Imaging tests may also be recommended for patients with headache:

- That wakes them at night

- A sudden or severe headache, or a headache that is the worst headache of someone's life

- New headaches in adults over 50 years, especially in the elderly. In this age group, it is particularly important to first rule out age-related disorders including stroke, low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), accumulation of fluid within the brain (hydrocephalus), and head injuries (usually from falls).

- Worsening headache or headaches that do not respond to routine treatment.

Symptoms that Could Indicate a Serious Underlying Condition

Headaches indicating a serious underlying problem, such as cerebrovascular disorder or malignant hypertension, are uncommon. (It should be emphasized that a headache without other neurologic symptoms is not a common symptom of a brain tumor.) People with existing chronic headaches, however, might miss a more serious condition by believing it to be one of their usual headaches. Such patients should call a doctor promptly if the quality of a headache or accompanying symptoms has changed. Everyone should call a doctor for any of the following symptoms:

- Sudden, severe headache that persists or increases in intensity over the following hours, sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or altered mental states (possible hemorrhagic stroke)

- Sudden, very severe headache, worse than any headache ever experienced (possible indication of hemorrhage or a ruptured aneurysm)

- Chronic or severe headaches that begin after age 50

- Headaches accompanied by other symptoms, such as memory loss, confusion, loss of balance, changes in speech or vision, or loss of strength in or numbness or tingling in arms or legs (possibility of stroke or brain tumor)

- Headaches after head injury, especially if drowsiness or nausea are present (possibility of hemorrhage)

- Headaches accompanied by fever, stiff neck, nausea and vomiting (possibility of spinal meningitis)

- Headaches that increase with coughing or straining (possibility of brain swelling).

- A throbbing pain around or behind the eyes or in the forehead accompanied by redness in the eye and perceptions of halos or rings around lights (possibility of acute glaucoma)

- A one-sided headache in the temple in elderly people; the artery in the temple is firm and knotty and has no pulse; scalp is tender (possibility of temporal arteritis, which can cause blindness or even stroke if not treated)

- Sudden onset and then persistent, throbbing pain around the eye possibly spreading to the ear or neck unrelieved by pain medication (possibility of blood clot in one of the sinus veins of the brain)

Treatment Approaches

Migraine treatment involves both treating acute attacks when they occur and developing preventive strategies for reducing the frequency and severity of attacks.

Treating Migraine Attacks

Many effective headache remedies are available for treating a migraine attack. Still, many patients are treated with unapproved drugs, including opoids and barbiturates that can be potentially addictive or dangerous.

The main types of medications for treating a migraine attack are:

- Pain relievers [usually nonprescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen]

- Ergotamines

- Triptans

It is best to treat a migraine attack as soon as symptoms first occur. Doctors generally recommend:

- Start with nonprescription pain relievers for mild-to-moderate attacks. If migraine pain is severe, a prescription version of an NSAID may be recommended.

- A triptan is generally the next drug of choice.

- Ergotamine drugs tend to be less effective than triptans but are helpful for some patients.

- Depending on the severity of the attacks, and accompanying symptoms, the doctor may recommend taking a triptan or ergotamine drug in tablet, injection, or suppository form. The doctor may also prescribe specific medications for treating symptoms such as nausea.

Try to guard against medication overuse, which can cause a rebound effect. Nearly all pain relief drugs used for migraine can cause rebound headache, and patients should not take any the drugs more than 9 days per month. If you find that you need to use acute migraine treatment more frequently, talk to your doctor about preventive medications.

Preventing Migraine Attacks

Preventive strategies for migraine include both drug treatment and behavioral therapy or lifestyle adjustments.

Patients should consider using preventive migraine drugs if they have:

- Migraines that are not helped by acute treatment drugs

- Frequent attacks (more than once per week)

- Side effects from acute treatment drugs or contraindications to taking them

The main preventive drug treatments for migraine are:

- Beta-blocker drugs [usually propranolol (Inderal, generic) or timolol (Blocadren)]

- Anti-seizure drugs [usually divalproex (Depakote, generic), valproate (Depacon, generic) or topiramate (Topamax, generic)]

- Tricyclic antidepressants [usually amitriptyline (Elavil, generic)] or the dual inhibitor antidepressant venlafaxine (Effexor, generic)

- The triptan frovatriptan (Frova) for menstruation-associated migraine

OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injection is also approved for prevention of migraine but it appears to work best for chronic (not episodic) migraine.

Butterbur (Petasites hybridus) is an herbal remedy that may be effective for migraine prevention. It is recommended by the American Academy of Neurology.

A preventive medication strategy needs to be carefully tailored to an individual patient, taking into account the patient's medical history and co-existing medical conditions. These drugs can have serious side effects.

A preventive medication is usually started at a low dose, and then gradually increased. It may take 2 - 3 months for a drug to achieve its full effect. Preventive treatment may be needed for 6 - 12 months or longer. Most patients take preventive medications on a daily basis, but some patients may use these drugs intermittently (for example, for preventing menstrual migraine).

Patients can also help prevent migraines by identifying and avoiding potential triggers, such as specific foods. Relaxation therapy and stress reduction techniques may also help. (See Lifestyle section in this report.)

Treatment Approaches for Children

Migraine Treatment for Children. Most children with migraines may need only mild pain relievers and home remedies (such as ginger tea) to treat their headaches. The American Academy of Neurology's practice guidelines for children and adolescents recommend the following drug treatments:

- For children age 6 years and older, ibuprofen (Advil, generic) is recommended. Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) may also be effective. Acetaminophen works faster than ibuprofen, but the effects of ibuprofen last longer.

- For adolescents age 12 years and older, sumaptriptan (Imitrex) nasal spray is recommended.

Migraine Prevention for Children. Non-medicinal methods, including biofeedback and muscle relaxation techniques, may be helpful. If these methods fail, then preventive drugs may be used, although evidence is weak on the effectiveness of standard migraine preventive drugs in children.

Withdrawing from Medications

If medication overuse causes rebound migraines to develop, the patient cannot recover without stopping the drugs. (If caffeine is the culprit, a person may need only to reduce coffee or tea drinking to a reasonable level, not necessarily stop drinking it altogether.) The patient can usually stop abruptly or gradually. The patient should expect the following:

- Most headache drugs can be stopped abruptly, but the patient should talk to their doctor first. Certain non-headache medications, such as anti-anxiety drugs or beta-blockers, require gradual withdrawal under medical supervision.

- If the patient chooses to taper off standard headache medications, withdrawal should be completed within 3 days.

- The patient may take other pain medicines during the first days. Examples of drugs that may be used include dihydroergotamine (with or without metoclopramide), NSAIDs (in mild cases), corticosteroids, or valproate.

- Patients should expect their headaches to get worse after they stop taking their medications, no matter which method they use. Most people feel better within 2 weeks, although headache symptoms can persist up to 16 weeks (and in rare cases even longer).

- If the symptoms do not respond to treatment and cause severe nausea and vomiting, the patient may need to be hospitalized.

Medications for Treating Migraine Attacks

Many different medications are used to treat migraines. Some migraines respond to non-prescription pain relievers such as ibuprofen, acetaminophen, naproxen, or aspirin. Among prescription drugs, triptans and ergotamine are the only types of medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for migraine treatment.

Other types of drugs, including opioids and barbiturates, are sometimes prescribed off-label for migraine treatment. Opioids and barbiturates have not been approved by the FDA for migraine relief, and they can be addictive.

All FDA-approved migraine treatments are approved only for adults. No migraine products have officially been approved for use in children.

Pain Relievers

Some patients with mild migraines respond well to over-the-counter (OTC) painkillers, particularly if they take a full dose of the medicine at the very first sign of an attack. OTC pain relievers, also called analgesics, include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic), naproxen (Aleve, generic), and aspirin. Products marketed as Advil Migraine or Motrin Migraine Pain are simply ibuprofen in a liquid-filled capsule.

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic). Excedrin Migraine contains a combination of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine.

There are also prescription-only NSAIDs such as diclofenac (Cataflam, generic).

NSAID Side Effects. High dosages and long-term use of NSAIDs can increase the risk for heart attack, stroke, kidney problems, and stomach bleeding. Aspirin does not increase the risk for heart problems, but it can cause other NSAID-related side effects. Frequent or daily use of NSAIDs may worsen migraines and lead to the development of medication overuse headache.

Triptans

Triptans (also referred to as serotonin agonists) were the first drugs specifically developed for migraine treatment. They are the most important migraine drugs currently available. They help maintain serotonin levels in the brain. Serotonin is one of the major brain chemicals involved in migraines.

Triptans are recommended as first-line drugs for adult patients with moderate-to-severe migraines when NSAIDs are not effective. Triptans have the following benefits:

- They are effective for most patients with migraine, as well as patients with combination tension and migraine headaches.

- They do not have the sedative effect of other migraine drugs.

- Withdrawal after overuse appears to be shorter and less severe than with other migraine medications

Sumatriptan. Sumatriptan (Imitrex, generic) has the longest track record and is the most studied of all triptans. It is available as a fast-dissolving pill, nasal spray, or injection. Injected sumatriptan works the fastest of all the triptans and is the most effective, but it can cause pain at the injection site. The nasal spray form bypasses the stomach and is absorbed more quickly than the oral form. Some patients report relief as soon as 15 minutes after administration. The spray tends to work less well when a person has nasal congestion from cold or allergy. It may also leave a bad taste. Sumatriptan is effective for many patients, but for some people headache recurs within 24 hours after taking the drug.

Other Triptans. Newer triptans include almotriptan (Axert), zolmitriptan (Zomig), naratriptan (Amerge, generic), rizatriptan (Maxalt), frovatriptan (Frova), and eletriptan (Relpax). Treximet combines in one pill both sumatriptan and the anti-inflammatory pain reliever naproxen (Aleve, generic). Frovatriptan is also recommended for prevention of menstrual migraine, and naratriptan and zolmitriptan may possibly be effective.

Although triptans, (like all migraine medications), are approved only for adults, researchers are investigating zolmitriptan for treating migraines in adolescents.

Side Effects. Side effects of triptans may include:

- Tingling and numbness in the toes

- Sensations of warmth

- Discomfort in the ear, nose, and throat

- Nausea

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Muscle weakness

- Heaviness or pain in the chest (especially with sumatriptan)

- Rapid heart rate

Complications of Triptans. The following are potentially serious problems.

- Complications of heart and circulation. Triptans narrow (constrict) blood vessels. Because of this effect, spasms in the blood vessels may occur and cause serious side effects, including stroke and heart attack. Such events are rare, but patients with an existing history or risk factors for these conditions should generally avoid triptans.

- Serotonin syndrome. Serotonin syndrome is a life-threatening condition that occurs from an excess of the brain chemical serotonin. Triptan drugs used to treat migraine, as well as certain types of antidepressant medications, can increase serotonin levels. These antidepressant drugs include serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) -- such as fluoxetine (Prozac, generic), paroxetine (Paxil, generic), and sertraline (Zoloft, generic) -- and selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as duloxetine (Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (Effexor, generic). It is very important that patients not combine a triptan drug with a SSRI or SNRI drug. Serotonin syndrome is most likely to occur when starting or increasing the dose of a triptan or antidepressant drug. Symptoms include restlessness, hallucinations, rapid heartbeat, tremors, increased body temperature, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. You should seek immediate medical care if you have these symptoms.

The following people should avoid triptans or take them with caution and only under a doctor's supervision:

- Anyone with a history or any risk factors for stroke, uncontrolled diabetes, high blood pressure, or heart disease.

- People taking antidepressants that increase serotonin levels.

- Children and adolescents. They may be safe, but controlled studies are needed to confirm this. (Triptans should not, in any case, be the first-line treatment for children.)

- People with basilar or hemiplegic migraines. (Triptans are not indicated for these migraineurs.)

- There is no evidence to date of any higher risk for birth defects in pregnant women who take triptans. Still, women should be cautious about taking any medications during pregnancy and discuss any possible adverse effects with their doctors.

Ergotamine (Ergot)

Drugs containing ergotamine (commonly called ergots) constrict smooth muscles, including those in blood vessels, and are useful for migraine. They were the first anti-migraine drugs available. Ergotamine is available by prescription in the following preparations:

- Dihydroergotamine (DHE) is an ergot derivative. It is administered as a nasal spray form (Migranal) or by injection, which can be performed at home.

- Ergotamine is available as tablets taken by mouth, tablets taken under the tongue (sublingual), and rectal suppositories. Some of the tablet forms of ergotamine contain caffeine.

Ergotamine's role since the introduction of triptans is now less certain. Only the rectal forms of ergotamine are superior to rectal triptans. Injected, oral, and nasal-spray forms are all inferior to the triptans. Ergotamine may still be helpful for patients with status migrainous or those with frequent recurring headaches.

Side Effects. Side effects of ergotamine include:

- Nausea

- Dizziness

- Tingling sensations

- Muscle cramps

- Chest or abdominal pain

The following are potentially serious problems:

- Toxicity. Ergotamine is toxic at high levels.

- Adverse effects on blood vessels. Ergot can cause persistent blood vessel contractions, which may pose a danger for people with heart disease or risk factors for heart attack or stroke.

- Internal scarring (fibrosis). Scarring can occur in the areas around the lungs, heart, or kidneys. It is often reversible if the drug is stopped.

The following patients should avoid ergots:

- Pregnant women. Ergots can cause miscarriage.

- People over age 60.

- Patients with serious, chronic health problems, particularly those with heart and circulation conditions.

Ergotamine can interact with other medications, such as antifungal drugs and some antibiotics. All ergotamine products approved by the FDA contain a "black box" warning in the prescription label explaining these drug interactions. The five FDA-approved ergotamine products are:

- Migergot suppository (marketed by G and W Labs)

- Ergotamine Tartrate and Caffeine tablets (marketed by Mikart and West Ward)

- Cafergot tablets (marketed by Sandoz)

- Ergomar sublingual tablets (marketed by Rosedale Therapeutics)

Opioids

If migraine pain is very severe and does not respond to other drugs, doctors may try painkillers containing opioids. Opioid drugs include morphine, codeine, meperidine (Demerol, generic), and oxycodone (Oxycontin)]. Butorphanol is an opioid in nasal spray form that may be useful as a rescue treatment when others fail.

Opioids are not approved for migraine treatment and should not be used as first-line therapy. Nevertheless, many opioid products are prescribed to patients with migraine, sometimes with dangerous results. For example, following reports of several drug-related deaths, the FDA warned that the cancer pain pill fentanyl (Fentora, generic) should not be used to treat patients with migraine or others conditions for which the drug is not specifically approved.

Side Effects. Side effects for all opioids include drowsiness, impaired judgment, nausea, and constipation. There is a risk for addiction, and these drugs can become ineffective with long-term use for chronic migraines. Doctors should not prescribe opioids to patients at risk for drug abuse, including those with personality or psychiatric disorders.

Drugs Used for Nausea and Vomiting

Metoclopramide (Reglan, generic) is used in combination with other drugs to treat the nausea and vomiting that sometimes occur either as a medication side effect or migraine symptom. Metoclopramide and other anti-nausea drugs may help the intestine better absorb migraine medications.

Medications for Preventing Migraine Attacks

The FDA’s approved drugs for prevention of migraine are:

- Propanolol (Inderal, generic)

- Timolol (Blocadren)

- Divalproex sodium (Depakote, generic)

- Valproate sodium (Depacon, generic)

- Valproic acid (Stavzor, Depakene, generic)

- Topiramate (Topamax, generic)

- OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox)

Propanolol and timolol are beta-blocker drugs. Divalproex, valproate, valproic acid, and topiramate are anti-seizure drugs. Many other drugs are also being used or investigated for preventing migraines.

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers are usually prescribed to reduce high blood pressure. Some beta blockers are also useful in reducing the frequency of migraine attacks and their severity when they occur. Propranolol (Inderal, generic) and timolol (Blocadren) are approved specifically for prevention of migraine. Metoprolol (Lopressor, generic) is also recommended and atenolol (Tenormin, generic), and nadolol (Corgard, generic) may also be considered for migraine prevention.

Side Effects. Side effects may include:

- Fatigue and lethargy are common.

- Some people experience vivid dreams and nightmares, depression, and memory loss.

- Dizziness and lightheadedness may occur upon standing.

- Exercise capacity may be reduced.

- Other side effects may include cold extremities (legs, arms, feet, hands), asthma, decreased heart function, gastrointestinal problems, and sexual dysfunction.

If side effects occur, the patient should call a doctor, but it is extremely important not to stop the drug abruptly. Some evidence suggests that people with migraines who have had a stroke should avoid beta blockers.

Anti-Seizure Drugs

Anti-seizure drugs, also called anticonvulsant drugs, are commonly used for treating epilepsy and bipolar disorder. Divalproex sodium (Depakote, Depakote ER, generic), valproic acid (Stavzor, Depakene, generic) and topiramate (Topamax, generic) are the only anti-seizure drugs that are approved for migraine prevention.

Side Effects. Anti-seizure medication side effects vary by drug but may include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Cramps

- Tingling sensation in arms and legs

- Hair loss

- Dizziness

- Sleepiness

- Blurred vision

- Weight gain (or with topiramate, weight loss)

- Valproate and divalproex can cause serious side effects of inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) and damage to the liver

Divalproex sodium, valproic acid, and topiramate can increase the risk for birth defects, particularly cleft palate and cognitive development. These drugs should not be used during the first trimester of pregnancy. Women who are of child-bearing age and considering pregnancy should discuss the safety of these drugs with their doctors and consider other types of migraine preventive medication.

All anti-seizure drugs can increase the risks of suicidal thoughts and behavior (suicidality). The highest risk of suicide can occur as soon as 1 week after beginning drug treatment and can continue for at least 24 weeks. Patients who take these drugs should be monitored for signs of depression, changes in behavior, or suicidality. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #44: Epilepsy.]

Tricyclics and Other Antidepressants

Amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep, generic), a tricyclic antidepressant drug, has been used for many years as a first-line treatment for migraine prevention. It may work best for patients who also have depression or insomnia. Tricyclics can have significant side effects, including disturbances in heart rhythms, and can be fatal in overdose. Although other tricyclic antidepressants may have fewer side effects than amitritpyline, they do not appear to be particularly effective for migraine prevention.

Venlafaxine (Effexor, generic) is another antidepressant recommended for migraine prevention. It is a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine (Prozac, generic), do not appear to be effective for migraine prevention.

Botox Injections

OnabtulinumtoxinA (Botox) is now approved for preventing chronic migraine in adults. Botox is given by multiple injections to the head and neck area about every 12 weeks. These injections may help to dull future headache symptoms. Botox appears to work best for chronic migraines. It has not been shown to work for migraines that occur less frequently than 14 days a month or for other types of headaches (such as tension headaches). The most common side effects are neck pain and headache.

Other Treatments for Preventing Migraines

Other types of medications and treatments are being used or investigated for prevention of migraines.

Triptans. Frovatriptan is effective for prevention of menstrual migraines. Naratriptan (Amerge, generic) and zolmitriptan (Zomig) may also be helpful.

NSAIDs. Certain over-the-counter and prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be helpful for migraine prevention. They include naproxen (Aleve, generic), ibuprofen (Aleve, Motrin, generic), fenoprofen (Nalpron), and ketoprofen (Nexcede, generic). However, daily use of NSAIDs can cause stomach problems and may also lead to a condition called medication overuse headache.

ACE Inhibitors. Commonly used for treating high blood pressure, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors such as lisinopril (Prinivil, generic) block the production of the protein angiotensin, which constricts blood vessels and may be involved in migraine.

Angiotensin-Receptor Blockers. Angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), such as candesartan (Atacand), are another type of high blood pressure medications being studied for migraine prevention.

Histamine. Subcutaneous (under the skin) injections of histamine may be helpful for migraine prevention.

Neurostimulation Devices. Researchers are investigating a transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) device to help stop migraines before they occur. The hair dryer-size device is held to the back of the head and delivers quick magnetic pulses. The device is used when a patient experiences the first signs of a migraine. Other types of nerve stimulation devices are also under investigation.

Nasal Devices. New types of nasal sprays and powders are being researched. Some of them use capsaicin, the chemical found in cayenne peppers, to help relieve pain.

Herbs and Dietary Supplements. Certain herbs and dietary supplements may be helpful for migraine prevention. See Non-Drug Treatments and Lifestyle Changes section of this report.

Non-Drug Treatments and Lifestyle Changes

There are several ways to prevent migraine attacks. You should first try a healthy diet, the right amount of sleep, and non-drug approaches (such as biofeedback) for prevention.

Behavioral Treatments

Behavioral techniques that reduce stress and empower the patient may help some people with migraines. They generally include:

- Biofeedback therapy

- Relaxation techniques

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Behavioral methods may help counteract the tendency for muscle contraction and uneven blood flow associated with some headaches. They may be particularly beneficial for children, adolescents, pregnant and nursing women, and anyone who cannot take most migraine medications. Studies generally find that these techniques work best when used in combination with medications.

Biofeedback. Many studies have demonstrated that biofeedback is effective for reducing migraine headache frequency. Biofeedback training teaches the patient to monitor and modify physical responses, such as muscle tension, using special instruments for feedback.

Relaxation Therapy. Relaxation therapy techniques include relaxation response, progressive muscle relaxation, visualization, and deep breathing. Muscle relaxation techniques are simple and easy to learn, and can be effective. Some patients may also find that relaxation techniques combined with applying a cold compress to the forehead may help provide some pain relief during attacks. Some commercially available products use a pad containing a gel that cools the skin for several hours.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) teaches patients how to recognize and cope with stressors in their life. It can help patients understand how their thoughts and behavior patterns may affect their symptoms, and how to change the way the body responds to anticipated pain. CBT may be included with stress management techniques. Research indicates that CBT is most effective when combined with relaxation training or biofeedback.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a Chinese medicine technique that uses thin needles to stimulate specific points aligned with energy pathways in the body. Studies have showed mixed results on the benefits of acupuncture for preventing migraine.

Lifestyle Changes

Making a few minor changes in your lifestyle can make your migraines more bearable. Improving sleep habits is important for everyone, and especially those with headaches. What you eat also has a huge impact on migraines, so dietary changes can be extremely beneficial, too.

Avoid Food Triggers. Avoiding foods that trigger migraine is an important preventive measure. Common food triggers include monosodium glutamate (MSG), processed lunch meats that contain nitrates, dried fruits that contain sulfites, aged cheese, alcohol and red wine, chocolate, and caffeine. However, people’s responses to triggers differ. Keeping a headache diary that tracks diet and headache onset can help identify individual food triggers.

Eat Regularly. Eating regularly is important to prevent low blood sugar. People with migraines who fast periodically for religious reasons might consider taking preventive medications.

Stay Physically Active. Exercise is certainly helpful for relieving stress. An analysis of several studies reported that aerobic exercise in particular might help prevent migraines. It is important, however, to warm up gradually before beginning a session, since sudden, vigorous exercise might actually precipitate or aggravate a migraine attack.

Limit Estrogen-Containing Medications. Medications that contain estrogen, such as oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy, may trigger migraines or make them worse. Talk to your doctor about whether you should stop taking these types of medications or reduce the dosage.

Herbs and Supplements

Manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need Food and Drug Administration approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been several reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Patients should always check with their doctors before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) updated its guidelines on migraine prevention to include complementary treatments. Based on reviews of clinical studies, the AAN recommends:

- Butterbur (Petasites hybridus). Butterbur is a traditional herbal remedy used for many types of ailments, including migraine. The AAN considers butterbur “effective” and recommends it be offered for migraine prevention. Butterbur was the only non-drug treatment ranked by the AAN as having the highest proof of evidence (Level A) for effectiveness. Butterbur may cause an allergic reaction in people who are sensitive to ragweed and related plants.

- Feverfew. Feverfew is another well-studied herbal remedy for headaches. The AAN ranks feverfew as “probably effective” (Level B evidence) and recommends that it be considered for migraine prevention. Pregnant women should not take this herb as it may potentially harm the fetus.

- Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) and Magnesium. Riboflavin and magnesium are the two vitamin and mineral supplments ranked by the AAN as “probably effective”. Vitamin B2 is generally safe, although some people taking high doses develop diarrhea. Magnesium helps relax blood vessels. Some studies have reported a higher rate of magnesium deficiencies in some patients with migraine..

Although not specifically recommended by the AAN, other herbal and dietary supplements associated with migraine prevention include:

- Fish Oil. Some studies suggest that omega-3 fatty acids, which are found in fish oil, have anti-inflammatory and nerve protecting actions. These fatty acids can be found in oily fish, such as salmon, mackerel, or sardines. They can also be obtained in supplements of specific omega-3 compounds (DHA-EPA).

- Ginger. In general, herbal medicines should never be used by children or pregnant or nursing women without medical counsel. One exception may be ginger, which has no side effects and can be eaten or taken as a tea in powder or fresh form, as long as quantities are not excessive. Some people have reported less pain and frequency of migraines while taking ginger, and children can take it without danger. Ginger is also a popular home remedy for relieving nausea.

Resources

- www.headaches.org -- National Headache Foundation

- www.achenet.org -- American Headache Society

- www.aan.com -- American Academy of Neurology

- www.ninds.nih.gov -- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- www.clinicaltrials.gov -- Find clinical trials

References

Bigal ME, Lipton RB. What predicts the change from episodic to chronic migraine? Curr Opin Neurol. 2009 Jun;22(3):269-76.

Fenstermacher N, Levin M, Ward T. Pharmacological prevention of migraine. BMJ. 2011 Feb 18;342:d583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d583.

Gilmore B, Michael M. Treatment of acute migraine headache. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Feb 1;83(3):271-80.

Goadsby PJ. Pathophysiology of migraine. Neurol Clin. 2009 May;27(2):335-60.

Holland S, Silberstein SD, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Evidence-based guideline update: NSAIDs and other complementary treatments for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012 Apr 24;78(17):1346-53.

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Hayashino Y. Botulinum toxin A for prophylactic treatment of migraine and tension headaches in adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012 Apr 25;307(16):1736-45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.505.

Jackson JL, Shimeall W, Sessums L, Dezee KJ, Becher D, Diemer M, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010 Oct 20;341:c5222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5222.

Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, Hirtz D, Yonker M, Silberstein S, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004 Dec 28;63(12):2215-24.

Lewis DW, Winner P, Hershey AD, Wasiewski WW. Adolescent Migraine Steering Committee. Efficacy of zolmitriptan nasal spray in adolescent migraine. Pediatrics. 2007 Aug;120(2):390-6.

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF; AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007 Jan 30;68(5):343-9.

Loder E. Triptan therapy in migraine. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 1;363(1):63-70.

Machado RB, Pereira AP, Coelho GP, Neri L, Martins L, Luminoso D. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of migraine in users of combined oral contraceptives. Contraception. 2010 Mar;81(3):202-8. Epub 2009 Oct 28.

Naumann M, So Y, Argoff CE, Childers MK, Dykstra DD, Gronseth GS, et al. Assessment: Botulinum neurotoxin in the treatment of autonomic disorders and pain (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008 May 6;70(19):1707-14.

Nestoriuc Y, Martin A. Efficacy of biofeedback for migraine: a meta-analysis. Pain. 2007 Mar;128(1-2):111-27. Epub 2006 Nov 2.

Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Dodick D. Acute treatment and prevention of menstrually related migraine headache: evidence-based review. Neurology. 2008 Apr 22;70(17):1555-63.

Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, Buring JE, Lipton RB, Kurth T. Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009 Oct 27;339:b3914. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3914.

Sierpina V, Astin J, Giordano J. Mind-body therapies for headache. Am Fam Physician. 2007 Nov 15;76(10):1518-22.

Silberstein SD. Preventive migraine treatment. Neurol Clin. 2009 May;27(2):429-43.

Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012 Apr 24;78(17):1337-45.

Tepper SJ, Spears RC. Acute treatment of migraine. Neurol Clin. 2009 May;27(2):417-27.

|

Review Date:

12/17/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |